Learn how to develop and build on TON coming from the Ethereum (EVM) ecosystem.

Execution model

Asynchronous blockchain

A fundamental aspect of TON development is the asynchronous execution model. Messages sent by one contract take time to arrive at another, so the resulting transactions for processing incoming messages occur after the current transaction terminates.

Compared to Ethereum, where multiple messages and state changes on different contracts can be processed within the same atomic transaction, a TON transaction represents a state change only for one account and only for a processing of a single message. Even though in both blockchains a signed included-in-block unit is called a “transaction”, one transaction on Ethereum usually corresponds to several transactions on TON, that are processed over a span of several blocks.

| Action description | Ethereum | TON |

|---|

| Single message processing with state change on one contract | Message call or “internal transaction” | Transaction |

| Number of state changes and messages on different accounts produced from initial contract call | Transaction | Chain of transactions or “trace” |

-

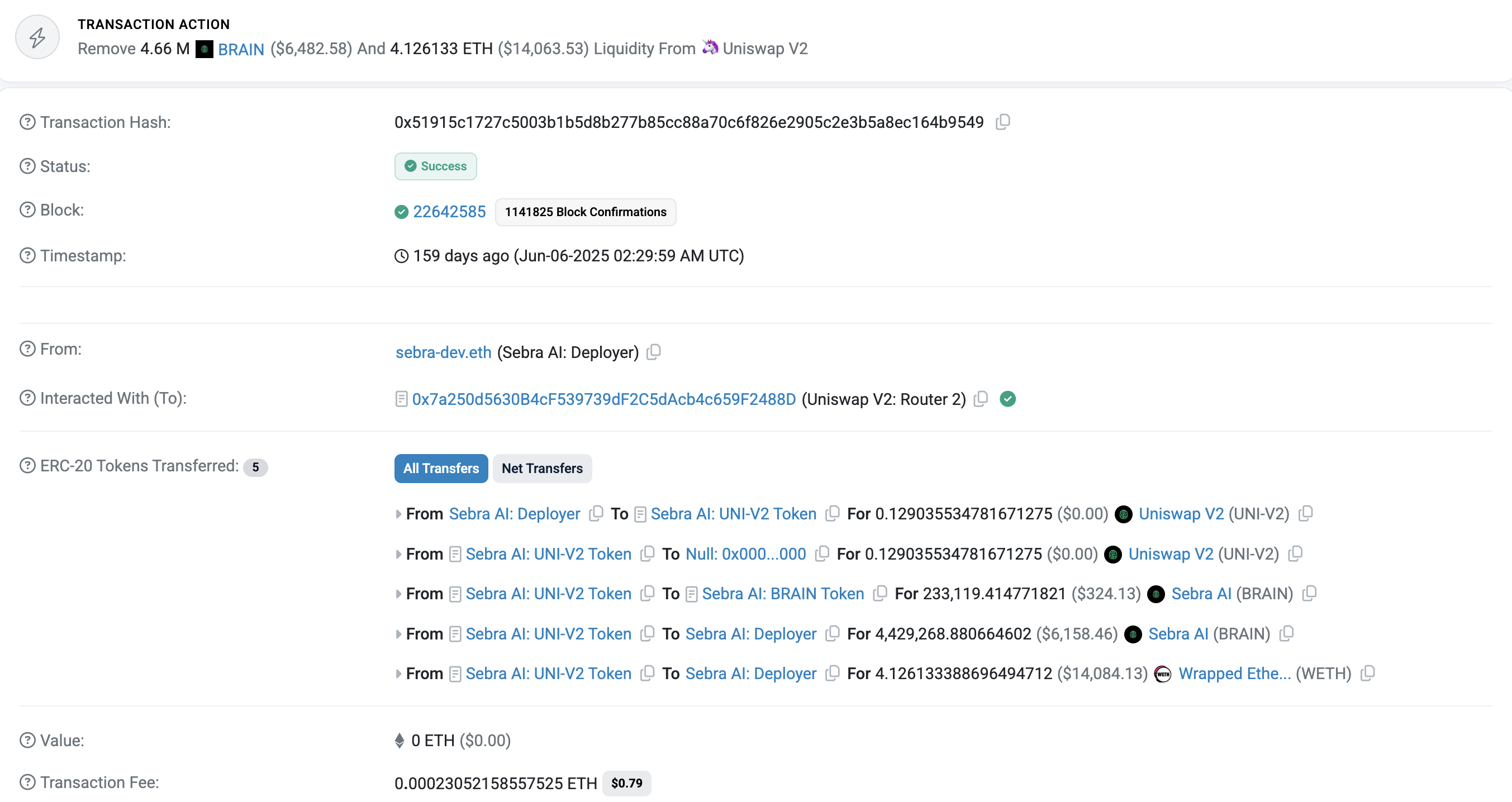

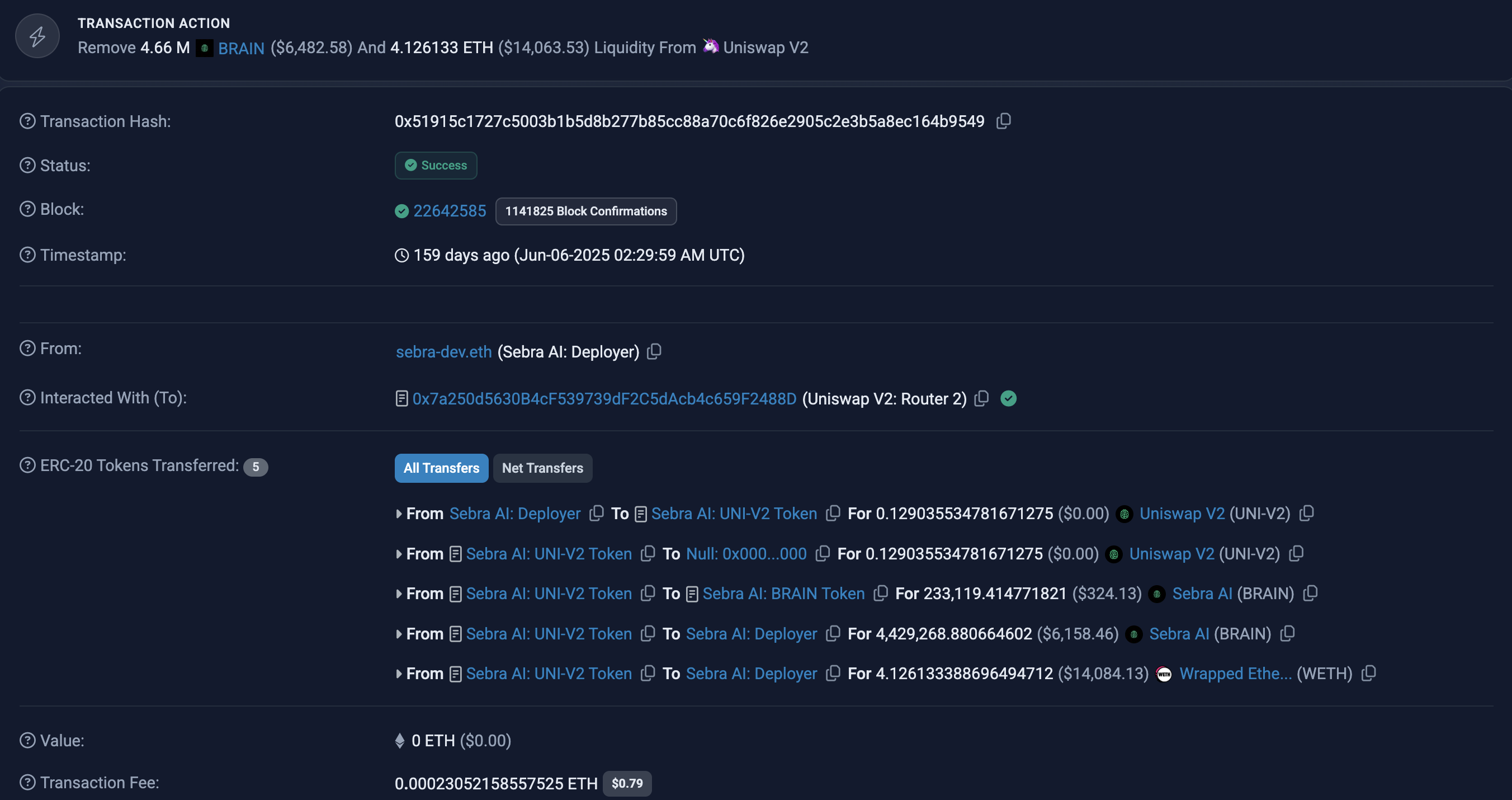

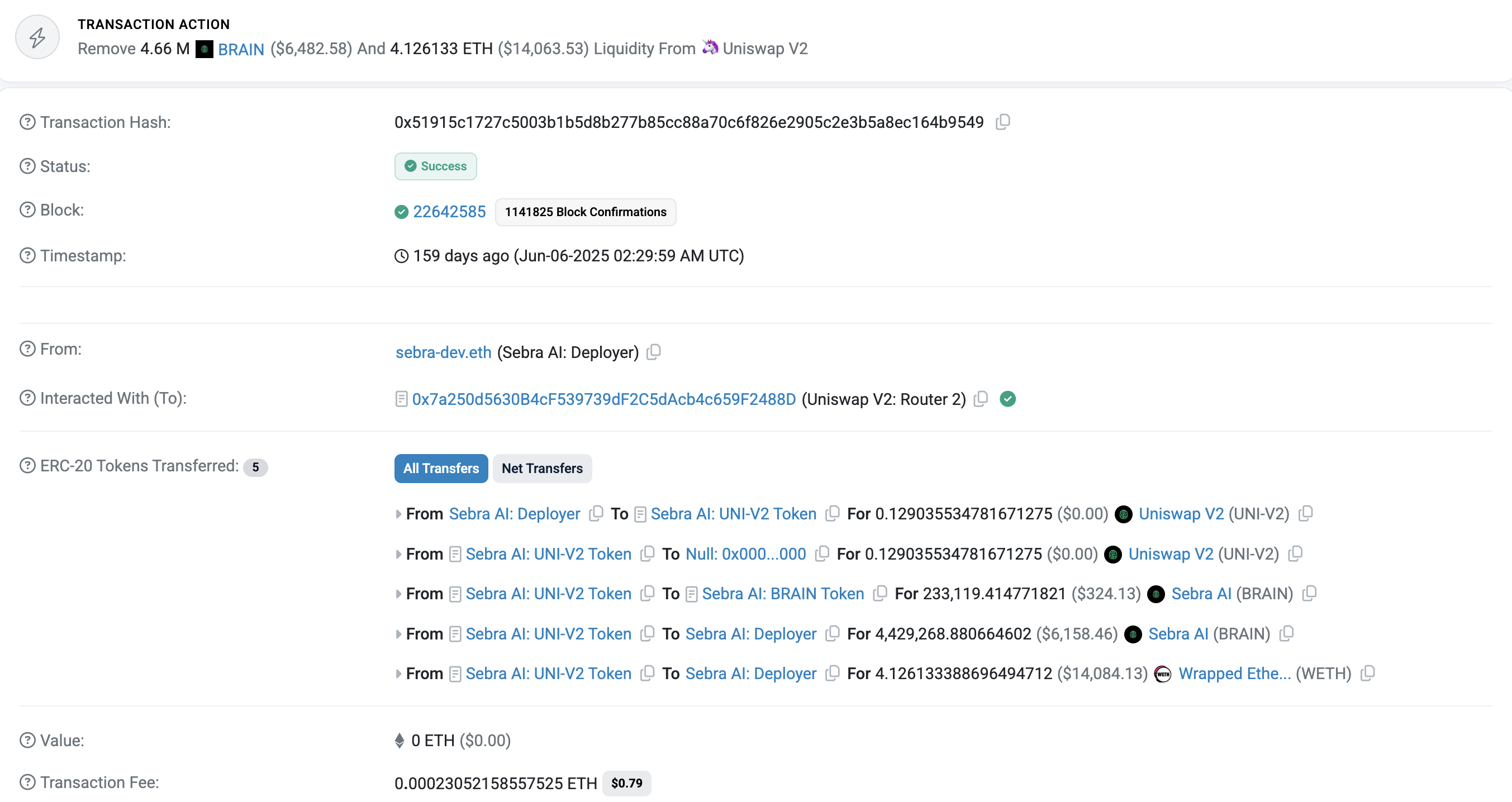

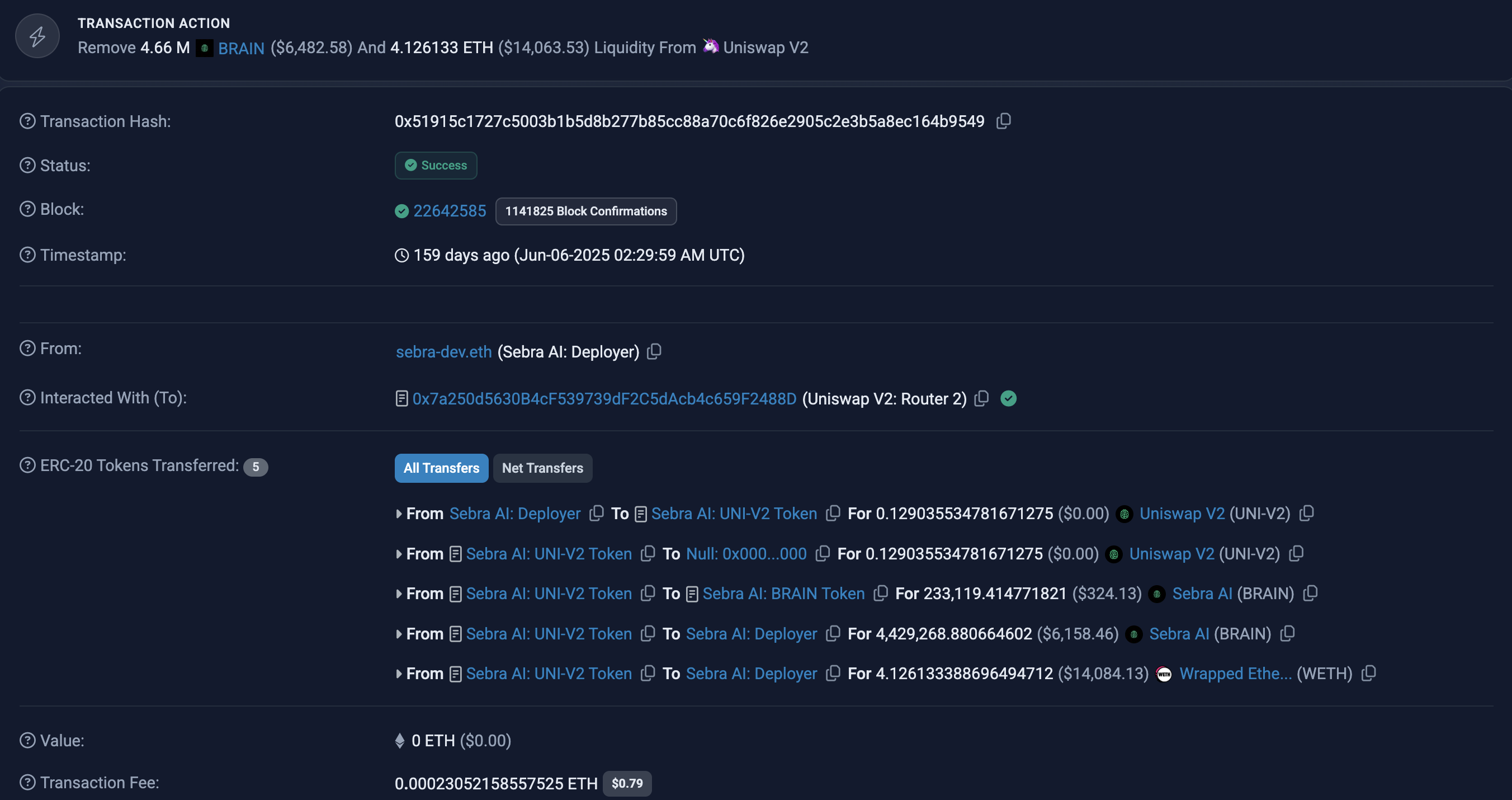

On Ethereum, it appears as a single atomic transaction with multiple contract calls inside it. This transaction has a single hash and is included in one block.

-

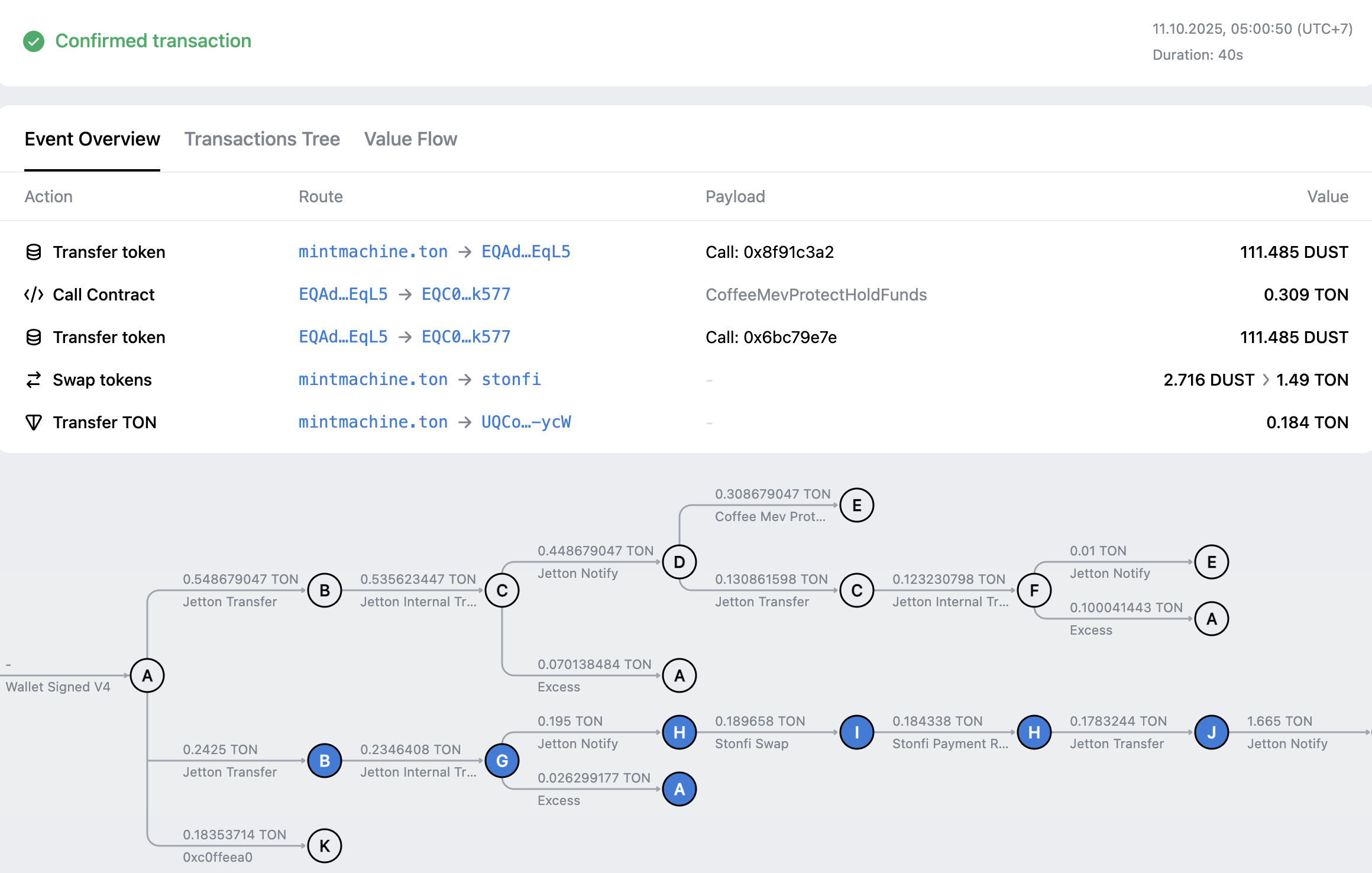

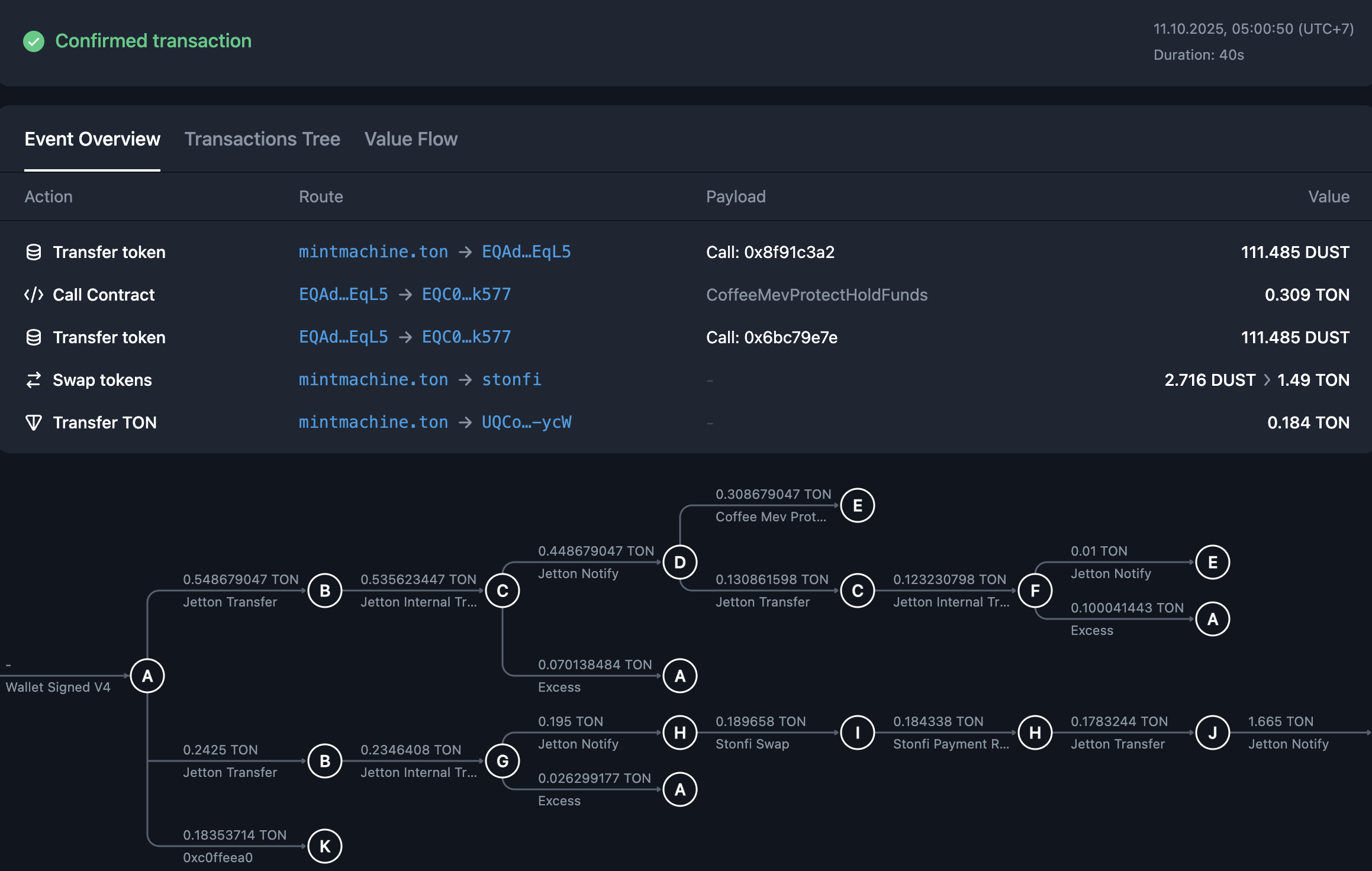

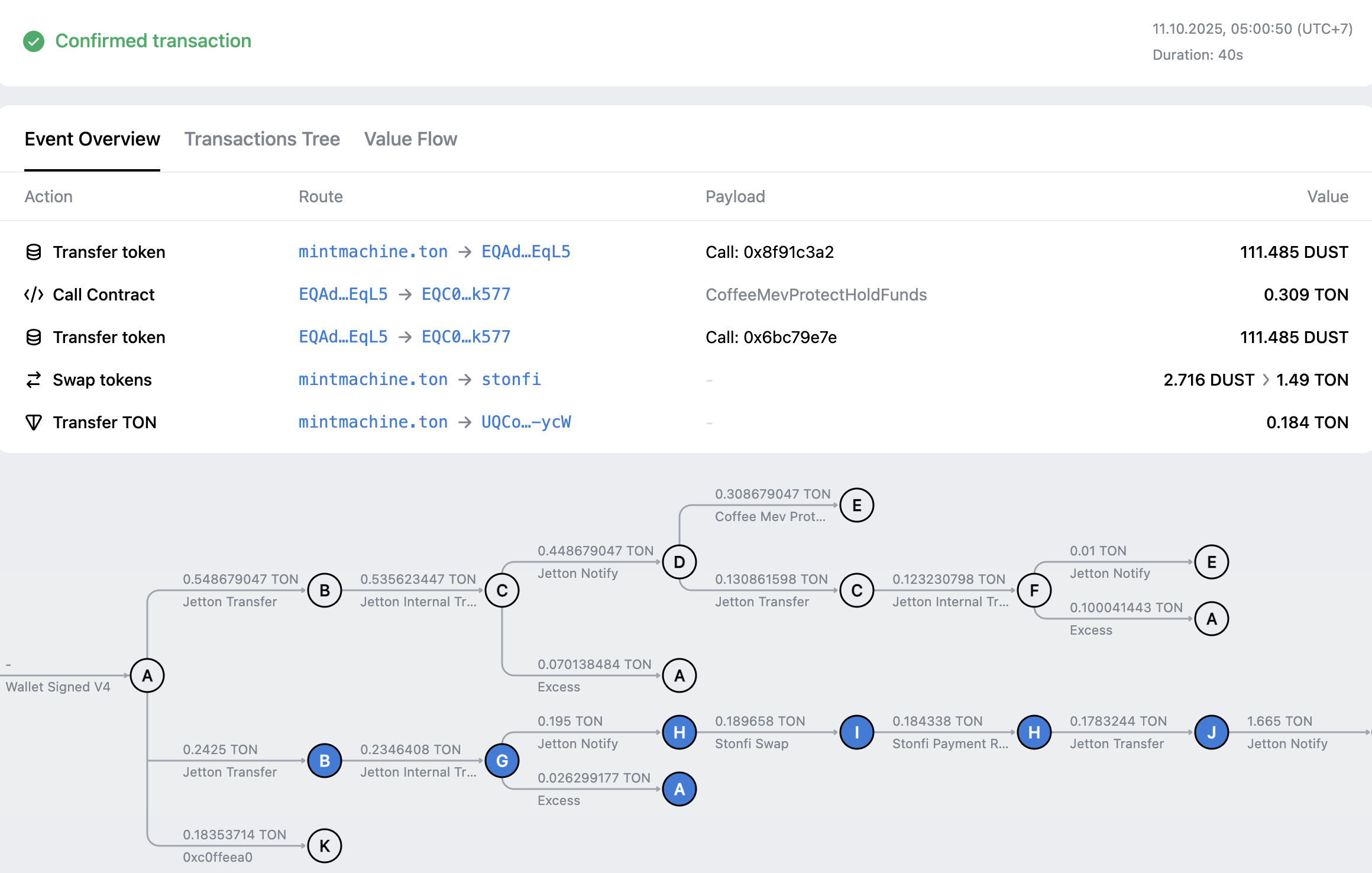

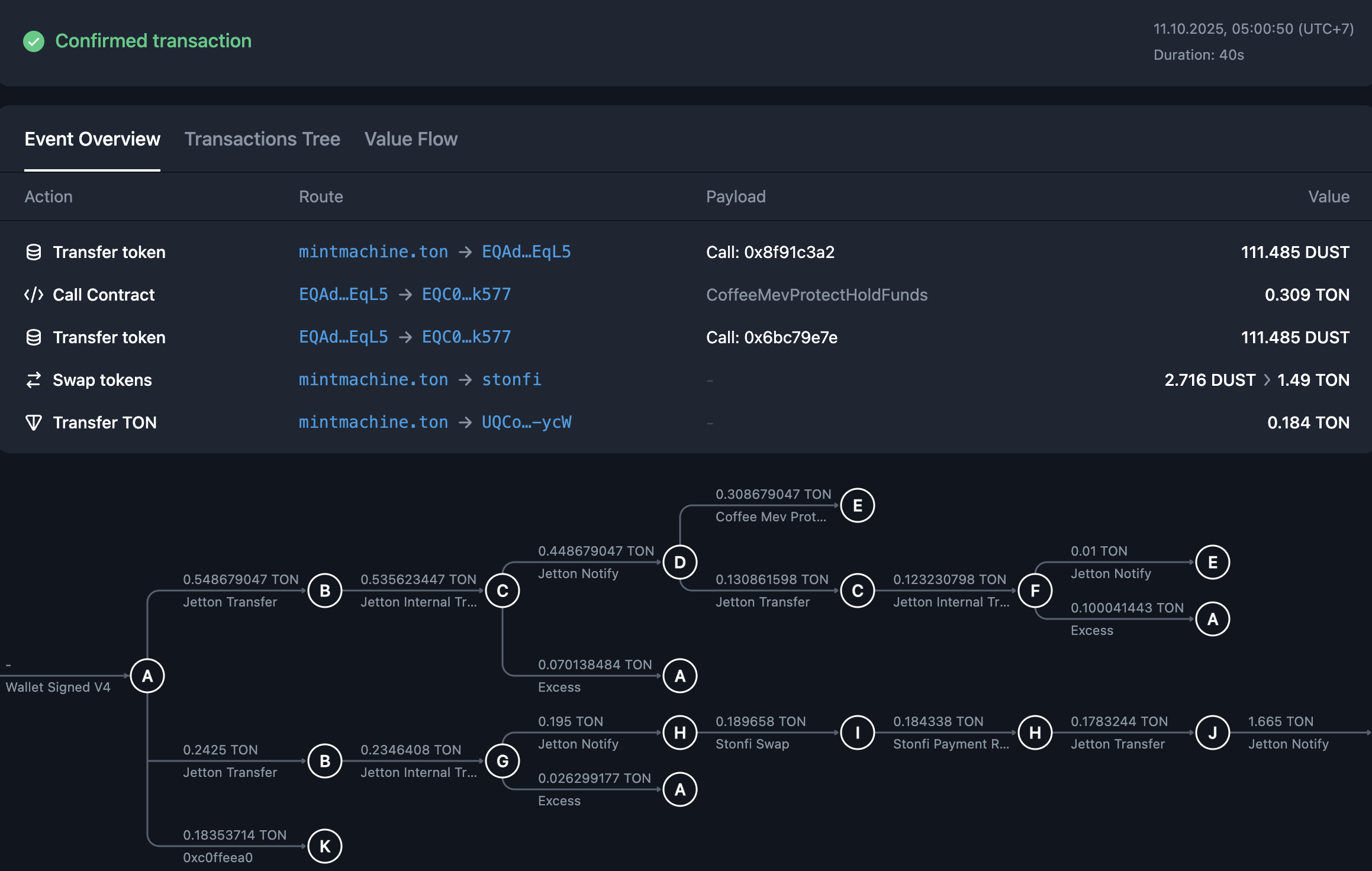

The same operation on TON consists of a sequence of more than 10 transactions. Each arrow on this image represents a distinct finalized transaction, with its own hash, inclusion block, and all the other properties:

Executing a large transaction on Ethereum or any other EVM-based blockchain comes with certain limitations: call depth of 1,024 nested calls and the block gas limit. With TON’s asynchronous execution model, a trace — a chain of transactions — can have any length, as long as there are enough fees to continue it. For example, the trace resulting from this message consisted of more than 1.5 million transactions, lasting more than 4,000 blocks until completion.

On-chain get methods

Another difference is in the get methods. Both Ethereum and TON support them, allowing data to be retrieved from contracts without paying fees. However, in TON, get methods cannot be called on-chain: a contract cannot synchronously retrieve data from another contract during a transaction. This is a consequence of TON’s asynchronous model: by the moment transaction that called a get method would start its execution, data might already change.

Account model

In Ethereum, there are two types of accounts: externally owned accounts (EOA), and contract accounts. EOAs are human-controlled entities, each represented by a private-public key pair. They sign transactions and each has its own balance; the community often refers to them as “wallets”.

In TON, there is no such separation. Every valid address represents an on-chain account, each with its own state and balance, that could be changed through transactions. This means that “wallets” in TON are smart contracts that operate under the same rules as any other contract on the blockchain.

The TON wallet smart contract works as a proxy: handles an external message, checks message is sent by the wallet’s owner using regular public-key cryptography, and sends an internal message somewhere further in the network.

Limited contract storage

In Ethereum, it’s possible to store any amount of data in a single contract. Unbounded maps and arrays are considered standard practice. TON sets a limit to the amount of data a contract can store. This means that ERC-20-like fungible tokens cannot be implemented in the same way as in an EVM chain, using a single map within a single contract.

The limit for contract storage is 65,536 unique cells contract storage, where a cell stores up to 1,023 bits. Messages are constrained by two size limits: 8,192 cells or 221 bits among them, whichever is smaller.

Every map that is expected to grow beyond 1,000 values is dangerous. In the TVM map, key access is asymptotically logarithmic, meaning that gas consumption continuously increases to find keys as the map grows.

Ecosystem

The recommended programming language for smart contract development in TON is Tolk. Other established languages are also used in the ecosystem; more information about them is available here.

For off-chain software, Typescript is the most adopted language in TON. Most of the tooling, bindings and SDKs are implemented in Typescript.

| Use case | Ethereum tool | TON counterpart |

|---|

| Blockchain interaction | Ethers, Web3.js, Viem | @ton/ton, Asset-sdk |

| Wallet connection protocol | Walletconnect, Wagmi | TonConnect |

| Dev environment framework / scripting | Hardhat, Truffle | Blueprint |

| Simulation engine | Revm & Reth | Sandbox |

@ton/core. Another library with wrappers for most important contracts and HTTP APIs is @ton/ton.

Services

Web3 developers often rely on specific products and services for on-chain development.

The following table showcases some use cases that existing TON services support.

| Use case | Ethereum service | TON service |

|---|

| User-friendly explorer | Etherscan | Tonviewer, Tonscan |

| Open-source dev explorer | Blockscout | TON Explorer |

| Debugger | Remix Debugger | TxTracer |

| IDE | Remix IDE | Web IDE |

| Asm playground and compilation explorer | EVM.Codes | TxTracer |

Standards

The table maps Ethereum standards and proposals, including ERC and EIP, to their TON counterparts, referred to as TEP.

Due to significant differences in execution models, most of the standards in TON differ significantly in semantics and general approach compared to their Ethereum analogs.

| Description | Ethereum standard | TON Standard (TEP) |

|---|

| Fungible token standard | ERC-20 | Jettons (TEP-0074) |

| Non-fungible token standard | ERC-721 | NFT standard (TEP-0062) |

| Token metadata | ERC-4955 (Not exactly, but close match) | Token Data Standard (TEP-0064) |

| NFT royalty standard | EIP-2981 | NFT Royalty Standard (TEP-0066) |

| DNS-like registry | ENS (EIP-137) | DNS Standard (TEP-0081) |

| Soulbound / account-bound token concept | EIP-4973 | SBT Standard (TEP-0085) |

| Wallet connection protocol | WalletConnect / EIP-1193 | TonConnect (TEP-0115) |